Posted: 09 March 2012

Successful interventions with new psychoactive substances- by Katy McCleod

While conducting training on new psychoactive substances throughout Scotland, I often get asked which interventions are the most effective for users of these substances. I recently came across the paper by the fabulous Dr Adam Winstock: New recreational drugs and the primary care approach to patients who use them (Winstock and Mitcheson, 2012) which provides insightful guidance on working with users. The paper can be downloaded for free at- Global Drug Survey Academic Articles.

Dr Adam Winstock is involved in some rather exciting projects connected to new psychoactive substances, namely the Global Drugs Survey published in Mixmag in March of every year and the brand new drugs meter app, more info can be found at http://globaldrugsurvey.com/ You can even catch him speaking at Crew’s national event CREWSUS in Perth later this month!

The paper explores interventions in primary care settings with Winstock and Mitcheson suggesting “a guiding communication style based on motivational interviewing”. This is certainly an approach we would advocate at Crew. As the paper describes “A good starting point is to assume that the patient might be ambivalent about change.” In Crew’s experience this is often the case. The very term “legal highs” which many users still apply, could arguably suggest use of these kind of substances is ‘safer’ than illicit substances to users. Teamed with a greater level of social acceptance for psychostimulants generally, it’s easy to see why a user may be ambivalent about change.

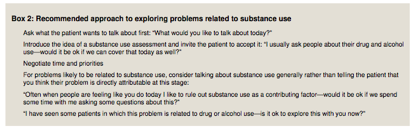

The key elements of motivational interviewing are its person centred and non judgemental approach which elicits motivation for change by providing feedback and rolls with any resistance encountered. As the paper explains “The key to motivational interviewing is to ascertain the patient’s concerns and respond accordingly; hold back from advocating change until a clearer picture is obtained”. The starting point for this is assessment, where it is crucial to establish the service users perception of the issues and most importantly what they wish to do about it. Depending on what setting you are working, one might expect if they have come forward to talk to you about it at all they may have at the very least a tiny seed of motivation for change. Of course it is possible the substance issue is not the key issue why that person has been referred and motivation for change may not be as immediately apparent. In these cases the recommended approach by Winstock and Mitcheson would be very effective:

(Winstock and Mitcheson, 2012).

In my own experience, the majority of clients would be willing to discuss substance use when it is introduced in this way. Where a client is completely resistant to talking about substance use as a problem, it may be that it is more appropriate to revisit at a later date rather than pursue at that time. Having introduced the topic and communicated to the client that any further discussions will move at their own pace, backing off is often very powerful and will make them far more likely to come to you when they do feel ready to discuss their use. The paper suggests ending any such interaction by seeking permission to review it again in the future. By doing this, you are making clear you are respecting the clients wishes not to discuss at this time but at the same time communicating that you are aware there may be a problem worthy of addressing.

Brief Interventions

MI techniques fit very well within brief interventions, something which the NHS has been applying to alcohol for a long time. Much of the NHS resources for alcohol brief interventions are transferable and adaptable to new psychoactive substances. There are many available at the Health Scotland website here. There’s also lots of good information available via SAMHSA in their Treatment Improvement Protocols collection, the brief intervention protocol is available here.

The paper goes on to highlight some useful techniques found in brief interventions including providing information and advice, feedback on risk, offering choices (menu of options) and signposting or referring. Where we have established problems related to drug use with a client, the paper suggests service users are more likely to be receptive to “expert information”. This could be described by specialist information given by the staff member gleaned from their knowledge and experience. It goes on to give an example: “When people use stimulants over a weekend and don’t get any sleep, it can lead to a reduction in the chemicals in your brain that help keep our mood stable and feeling happy”. Again this fits with Crew’s experience, through our client work we find the majority are very receptive to specialist information and often ask more detailed questions once rapport has been built. It is vital that the rapport is kept intact at this stage and it doesn’t fall into the “expert trap”, which is to be avoided within MI. The paper makes an excellent yet simple suggestion for this by suggesting “eliciting the patient’s response to that information (“How does that fit with your experience?”)” This simple open question communicates value and is likely to open up the interaction to change talk.

Another useful tool is the decisional balance. This is basically looking at reasons for and against change. This is done by exploring the costs of change against the benefits of change and then the costs of staying the same against the benefits of staying the same. You can talk this through with a client or you may find it useful to use a worksheet within the session so that you can compare the costs and benefits.

The paper also outlines some useful ways of broaching the subject of change:

“We’ve spoken about some of the concerns you have and how your drug use might be related to this?, where do we go from here?” A direct question might be: “Would you like to do something about your drug use?”

If change is indeed established as a goal in accordance with the brief intervention structure, we must be clear of an exit strategy for the intervention, can we follow up with the client directly ourselves or is it more appropriate to signpost or refer on?

(If you are coming to CREWSUS, George Burton from STRADA will be joining me for the Legal HIghs & Emerging Trends plenary. STRADA also offer courses on MI & brief interventions. In Edinburgh, try NHS training.)

Harm Reduction

Where the client is more ambivalent to change, harm reduction advice (as the paper also identifies) is often an effective alternative. One of the key issues with new psychoactive substances is the lack of specialist knowledge, much of the knowledge base being taken from anecdotal reports. In these cases, we must refer to general safety tips and advice from other related substances. The paper describes this as ‘common sense advice”. Typical practical harm reduction advice for those determined to use may be around:

• Administration route- are there ways they can use more safely? E.g use rolled up card rather than money as tooter (snorting equipment) and don’t share with anyone else

• Test dosing- taking a very small amount and waiting an adequate amount of time before re-dosing. (some of the new psychoactives have delayed onsets so people should ideally be waiting 2 hours before re-dosing)

• Limit the amount they take in a drug using session

Other sensible advice as described in the paper is “reviewing the progression of any health concerns with a period of cessation, and total avoidance of the drug for people in high risk groups, such as those with pre-existing mental health issues.” Encouraging users to research the substance they are going to take is something we certainly do at Crew but as the paper correctly highlights, there are issues with user reports from Internet forums. They can be unreliable and are only one part of the picture.

Establishing Goals

Another approach I have found effective with this users group is solution focused therapy: there is a good article exploring its elements and uses here. The idea of focusing on solutions rather than problems is, again, very motivational. Techniques such as the miracle question and scaling questions are great at establishing goals both short and long term. In my experience, where someone is in the grips of problematic use, they can find it hard to establish aspirations and their self-efficacy may be non-existent. They are often not accustomed to being asked about their aspirations so this can be the start of a really powerful interaction.

The key for me is linking some of the more aspirational and long term goals into smaller and achievable goals. Again scaling questions can be used within this, for example “If 10 is where you want to be and 2 is where you are now, what things could you do to get you to move towards 3”. SMART goals are often effective here, so goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-based. If goal setting is applied correctly, it can be incredibly motivational. Where goals have not been achieved, it’s always worth reviewing them using the SMART framework as often it could be a case of simply moving too fast.

Though working with users of new psychoactives or legal highs can seem daunting for workers, the tools and techniques above can provide a framework for working effectively with a user of any substances.

Our drug counseling team will be providing some useful insights into other effective techniques in their workshop at the National event CREWSUS. Be sure to book your place now before you miss out! I’m also doing open workshop training in Aberdeen with the Incite team, April 24 & 25, please take a look.

Katy MacLeod,

Crew Training & Outreach Coordinator, CREW.

Want to book a ticket for CREWSUS online? Check here.